“You can’t get to the moon by piling up chairs.”

Published on: Wednesday May 23 2012

Computing pioneer Alan Kay tells us that a computer is “an instrument whose music is ideas.” This seems like a beautiful metaphor, until you realize that we have somehow ended up in a world where the profession of musician is nearly unknown. To continue with this analogy, let’s imagine that you were a child who loves music. A child with Mozart’s inclinations, if not necessarily the full magnitude of his gifts. Your parents buy you a toy piano, and you live out what are, unbeknownst to you, the brightest days of your life. The years go by, adulthood comes, and you become - no, not a composer: an organ grinder. (Or, if you like, a disk jockey.) Or let’s say that you were an extraordinary lucky and dedicated child of music. You manage to enroll in a conservatory. Or perhaps you don’t, but instead you spend your free time away from your organ-grinding day job as an amateur composer. And yet, in either case, you are still stuck playing out your original works on a hacked barrel organ. Why? It is because, in this imaginary nightmare world, the very idea of a musical instrument has faded away. If someone wishes to hear music, he turns a crank or listens to the results of someone else doing so. Or perhaps there are Victrolas in this world - and professional composers, the few which still exist, are expected to compose music by hand-etching grooves on a phonograph record, as if they were machinists working a peculiar sort of lathe.

Sadly, the above scenario is more truth than fiction - for computer enthusiasts. There is a particularly cruel discrepancy between what a creative child imagines the trade of a programmer to be like and what it actually is. When you are a teenager, alone with a (programmable) computer, the universe is alive with infinite possibilities. You are a god. Master of all you survey. Then you go to school, major in “Computer Science,” graduate - and off to the salt mines with you, where you will stitch silk purses out of sow’s ears in some braindead language, building on the braindead systems created by your predecessors, for the rest of your working life. There will be little room for serious, deep creativity. You will be constrained by the will of your master (whether the proverbial “pointy-haired boss,” or lemming-hordes of fickle startup customers) and by the limitations of the many poorly-designed systems you will use once you no longer have an unconstrained choice of task and medium. To my knowledge, no child grows up “playing doctor” and still believes as a teenager (or even as a college student) that an actual medical practice resembles that activity. Likewise, no one has a fully functional toy legal system to play with as a child, and as a result goes into law. On the other hand, “adult” programming, seen from afar, is enough like child-programming to set the computer-enthusiast child up for just this kind of exceptionally cruel bait-and-switch.

Let’s say that you were one of the lucky ones - those who found a way to pay their bills via something resembling creative programming. Or, far more likely, you inhabit the salt mines by day, while letting your mind run free in your spare time. Yet in both cases, you are doomed to work with the instruments of the salt mine! Fortunately, in software there is room for some liberating deviancy - since bits are easy to rearrange and copy. But as for hardware, you come home to the very same instrument of torture and mutilation you left behind in the cube farm: the typewriter keyboard. (And, naturally, the “C machine.” But the latter is an overworked subject on this blog, and today we speak of other things.)

Virtually every profession has a concept of professional equipment. It tends to be costlier, sturdier, more solid, more rewarding of dedicated training, more difficult to obtain, than equipment intended for amateurs. And yet, among the tools of a modern programmer’s trade, we find scarcely anything which fits into this category. Perhaps you are now sitting in front of your lovingly-maintained heirloom IBM “Model M” keyboard, but it is still a typewriter keyboard - and resembles, in many fundamental ways, the cheapest piece of disposable trashware found at your local electronics store.

Conventional wisdom in the technology community holds that the personal computer revolution gave everyone access to professional-grade computing equipment. I hold the opposite view: that the very notion of professional equipment has been forgotten in our field (and to my knowledge, in our field alone.)

If the above is a delusion, I am proud to share this delusion with several persons whose brilliant minds I think of as my guiding lights. Among them was Erik Naggum:

Why are we even _thinking_ about home computer equipment when we

wish to attract professional programmers? in _every_ field I know, the

difference between the professional and the mass market is so large that

Joe Blow wouldn’t believe the two could coexist. more often than not,

you can’t even get the professional quality unless you sign a major

agreement with the vendor — such is the investment on both sides of the

table. the commitment for over-the-counter sales to some anonymous

customer is _negligible_. consumers are protected by laws because of

this, while professionals are protected by signed agreements they are

expected to understand. the software industry should surely be no

different. (except, of course, that software consumers are denied every

consumer right they have had recognized in any other field.) …they don’t

make poles long enough for me want to touch Microsoft products, and I

don’t want any mass-marketed game-playing device or Windows appliance

_near_ my desk or on my network. this is my _workbench_, dammit,

it’s not a pretty box to impress people with graphics and sounds. when I

work at this system up to 12 hours a day, I’m profoundly uninterested in

what user interface a novice user would prefer.

Erik

Naggum, comp.lang.lisp. Feb. 16, 1997. (Emphasis mine.)

And so, here we are, deskilled craftsmen, flippers of bits. Some of us fungible today, some tomorrow. Still performing the same old menial tasks by mouse instead of by lever – the so-called Computer Revolution notwithstanding. Still “turning steam engine valves by hand.” Still writing the same, dreary boilerplate code, again and again. On QWERTY keyboards…

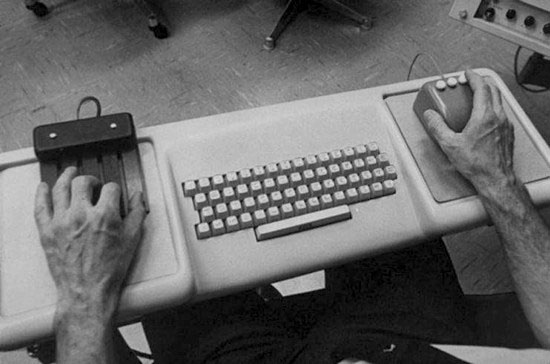

You have probably heard of Douglas Engelbart: one of the very, very few genuinely great minds of the computing field. He is best known as the inventor of the computer mouse - but in fact, this man created just about all of the conceptual underpinnings of what we now think of as the standard human-computer interface. Arguably, he is single-handedly responsible for the very notion of interactive, visual computing. Engelbart presented his ideas to the public in one long demo session on December 9, 1968. This demo is known today, quite appropriately, as “The Mother of All Demos.”

If you watch the Mother of All Demos - which you should - you will notice the piano-like device sitting to the left of the conventional keyboard:

A closer look:

In use:

(source)

The above gadget is known as a chorded

keyboard, or chorder. In Engelbart’s computing environment, it

supplemented, rather than replaced, the traditional typewriter

keyboard. Most of Engelbart’s contemporaries saw the chorder as a

somewhat naive engineering mistake. Among them was Alan Kay:*

*

In Alan Kay’s metaphor, the problem with bootstrapping in Douglas

Engelbart’s Augmentation Research Center was that while

“Engelbart, for better or for worse, was trying to make a

violin,” “most people don’t want to learn the violin.”

User-friendliness, not coevolutionary learning, became the norm in the

design of human-computer interfaces.

Thierry

Bardini, Bootstrapping: Douglas Engelbart, Coevolution, and the Origins

of Personal Computing. (p. 215.) (Emphasis mine.)

As far as I can tell, this is still the mainstream view today:

Today, human-computer interaction is focused on ease-of-use and

learnability. Ideally, people should be immediately effective with a

computer the first time they use it. The emphasis is on usability –

without the necessity of training. The exact opposite of Engelbart’s

approach. Engelbart’s dilemma is that his philosophy produced some of

the best computer technologies of our age (e.g. mouse, windows, word

processing, etc.), but the full realization of his vision is completely

counter to way interaction designers think of computers systems today.

In fact, Engelbart’s belief in efficiency over ease-of-use places him in

the fringe of computer interaction design today. That’s sad considering

he’s done more for interaction design than any else I can think

of.

Richard Monson-Haefel, “Engelbart’s Usability

Dilemma: Efficiency vs Ease-of-Use.”

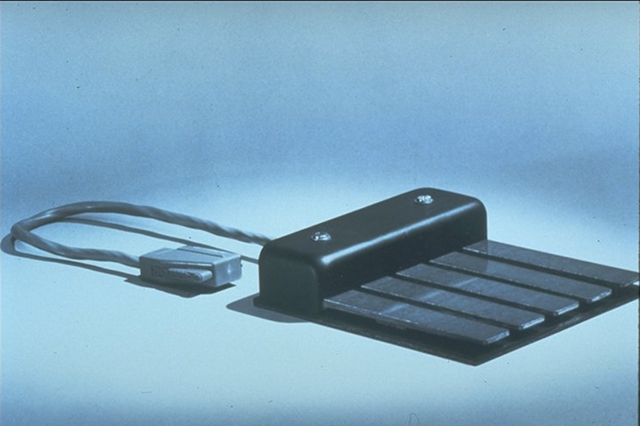

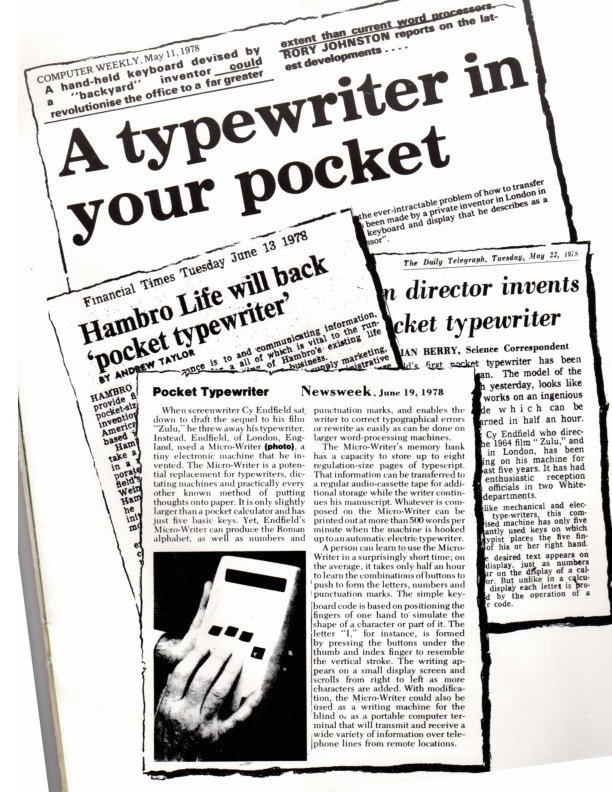

And yet, there were those who believed that there is something to be gained by breaking with the typewriter tradition. Why should the mechanical constraints of nineteenth-century clockwork limit today’s user interfaces? Among the few brave souls who “put their money where their mouth is” was Cy Endfield - American (later, British) screenwriter, film director, theatre director, author, magician and inventor. Endfield, a true polymath, created the Microwriter - a pocket word processor equipped with six keys, intended to be operated with one hand:

At first glance, this device resembles the familiar stenotype. However, the latter was never meant to be a general-purpose text entry system. Stenotypes use syllable-based encodings, narrowly specialized for transcribing human speech. Endfield’s Microwriter was something rather different: a genuinely-original, alphabet-based, general-purpose text entry system.

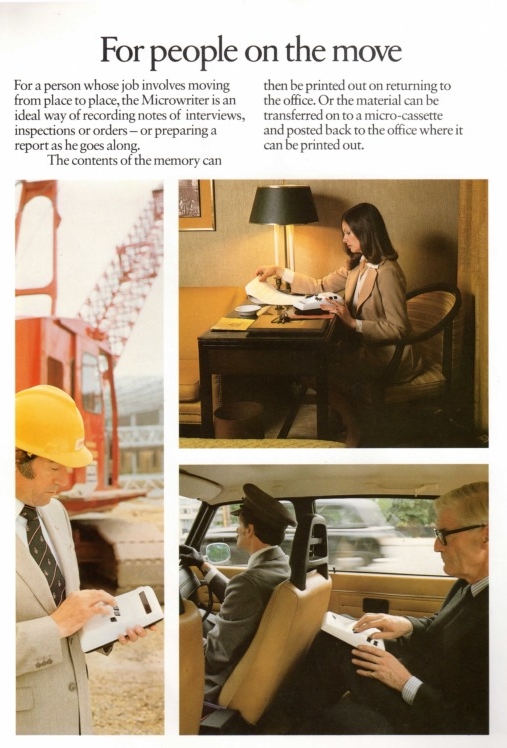

The Microwriter’s use of one - rather than both - hands seems like a shortcoming, until you realize that the device was designed for maximal portability - at the very dawn of the age of personal computing! It was really intended to replace a traditional paper clipboard, rather than a typewriter:

(Source)

(Source)

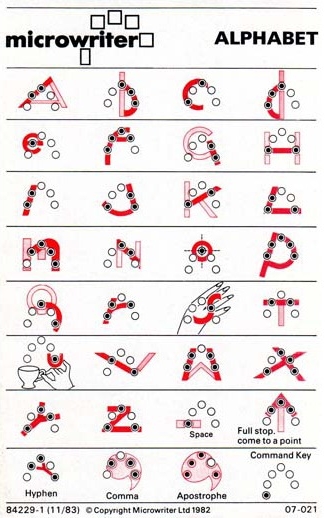

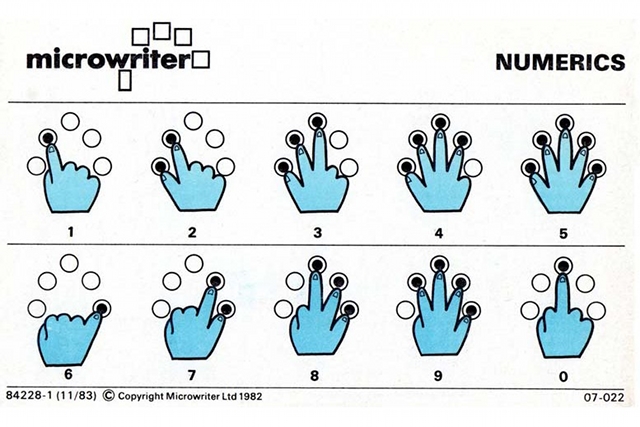

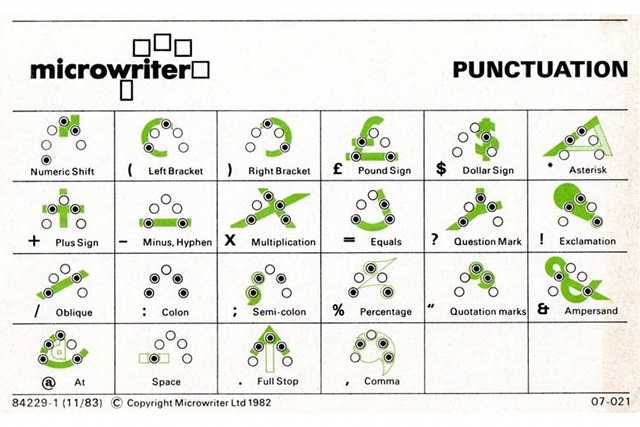

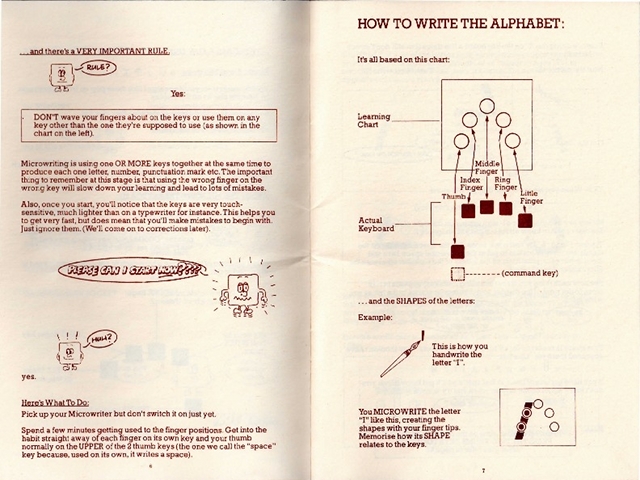

Endfield’s chording system was of a very elegant design, which balanced ergonomics with mnemonic simplicity:

Volume One of

the Microwriter User Guide contains a miniature crash-course in the

use of Endfield’s writing system. This document is perhaps the cleanest

and most imaginative piece of technical writing that I have ever come

across:

Volume One of

the Microwriter User Guide contains a miniature crash-course in the

use of Endfield’s writing system. This document is perhaps the cleanest

and most imaginative piece of technical writing that I have ever come

across:

There have been other commercial and academic attempts at chorded keyboards, but this one happens to be the earliest (that I am aware of) which reached actual production and was placed on the market (however briefly.) It is also the only one which I have had the good fortune to actually hold in my hands:

This rather unimpressive “hello world” was achieved after around fifteen minutes of practice. The speed is a fraction of my QWERTY typing speed, but is a near-match for my handwriting on a good day. What would it have been like if I had been put in front of an Endfield keyboard as a small child, instead of a typewriter monstrosity?

And what if you could expect to find (or carry) a decent, non-wrist-destroying chorded typing device everywhere you go, at work sites, schools, etc.? Clearly, that is not the kind of world we live in: century-old technological standards die hard. But why is there so little interest among genuinely-professional computer users in an input device which maximizes speed and slows the destruction of the hands with which you work? And I marvel at the absurdity of the miniature QWERTY keypads found on mobile phones! Surely that is where the supremacy of the chorder would be indisputable.

Fascinating as the chorded keyboard is, its confinement to the ghetto of “crackpot technology” is but a symptom of the underlying disease: the total victory of the technological business model which caters primarily to the unskilled.

Naggum clearly saw the absence of professional computing equipment for what it is: a result of the erosion of the very concept of the craftsman, the skilled, non-fungible professional:

something important happens when a previously privileged position

in society suddenly sees incredibly demand that needs to be filled,

using enormous quantities of manpower. that happened to programming

computers about a decade ago, or maybe two. first, the people will no

longer be super dedicated people, and they won’t be as skilled or even

as smart — what was once dedication is replaced by greed and sometimes

sheer need as the motivation to enter the field. second, an unskilled

labor force will want job security more than intellectual challenges (to

some the very antithesis of job security). third, managing an unskilled

labor force means easy access to people who are skilled in whatever is

needed right now, not an investment in people — which leads to the

conclusion that a programmer is only as valuable as his ability to get

another job fast. fourth, when mass markets develop, pluralism suffers

the most — there is no longer a concept of healthy participants: people

become concerned with the individual “winner”, and instead of people

being good at whatever they are doing and proud of that, they will want

to flock around the winner to share some of the glory.

Erik

Naggum, comp.lang.lisp. Jul. 15, 1999.

In the mind of today’s technological entrepreneur, the ideal user (and employee) is semi-skilled - or unskilled entirely. The ideal user interface for such a person never rewards learning or experience when doing so would come at the cost of immediate accessibility to the neophyte. This design philosophy is a mistake - a catastrophic, civilization-level mistake. There is a place in the world for the violin as well as the kazoo. Modern computer engineering is kazoo-only, and keyboards are only the most banal example of this fact. Far more serious - though less obvious - problems of this kind tie our hands and wastefully burn our “brain cycles.”

Professional equipment, whose mastery requires dedication and mental flexibility, may not be appropriate for casual users. But surely it is appropriate - in fact, necessary - for professionals? Just why is this idea confined to crackpots shouting in the wilderness? I hope to learn a definitive answer to this conundrum some day.

Edit:

Some people said, after reading this: “He thinks that computers ought to

be costly and difficult to use.” Sorry, idiots. The message here is that

a computer system should maximally reward learning.

(The way Emacs does.)

And that this should certainly be true of a computer one uses for 8-14

hours a day, for decades.

This entry was written by Stanislav , posted on Wednesday May 23 2012 , filed under Chorder, Distractions, Hardware, Hot Air, Idea, NonLoper, Philosophy, Photo, ShouldersGiants, SoftwareSucks . Bookmark the permalink . Post a comment below or leave a trackback: Trackback URL.

ASV says:

Wow, this is all interesting to me! I just recently noticed that there is software to do this on a touchscreen. Now I’m learning how to, thanks to you and metafilter.

Chris Rainey says:

I was the co-patent holder of Microwriting with Cy Endfield (film director - Zulu). 25000 people purchased the Microwriter and the follow on machine the AgendA which was a true pocket organiser, diary, alarm etc and was a fore runner to many of the current machines and was manufactured from 1987 to 1991. It only failed because of the economic downturn of the early 1990’s when Sir Mark Weinberg withdrew from the project after investing a lot of money in a new machine which over stretched the finances of the company. The CyKey (the name is a tribute to Cy Endfield) is still available as an add on to a PC or Mac and was developed to fill a gap and was developed by us here in Devon. Basic Microwriting can be mastered in about 20 minutes by most people because of very clever mnemonics which Cy created; based on something we all already know-the shape of the letters!

Stanislav says:

Dear Chris Rainey,

Thank you for your efforts in helping to create the Microwriter and its successors!

I am glad to learn that you are still in this business. I do, however, wish that the CyKey were a word processor like the Microwriter, rather than a PC keyboard replacement. Personally, I would pay good money for a modernized Microwriter-like gadget. There is great potential in dedicated, high-quality hardware created for a clear purpose. Consider, for instance, the Amazon Kindle. I would dearly love a dedicated word processor which is usable in bright sunlight (e-ink or the like) and runs for months on one battery charge, never crashes, presents no distractions, and, shortly, isn’t a PC. Not being a PC (or, more specifically, not running a PC operating system) is a truly under-rated and beautiful feature in any gadget.

Yours,

-Stanislav

Veky says:

I own a Kindle. I would like to bust a few myths here.

It is usable in bright sunlight, but only because you refresh the display once every few minutes (when you turn the page). Whenever you are entering text, it is so slowly updating to be almost unusable. That’s why newer e-ink systems have given up the keyboard entirely. Usable word processor on this device is impossible.

It doesn’t run for months on one charge if you really use it. (Amazon says: battery life projections are based on the assumption of half an hour of use a day. I mean, really? People don’t read for more than 30 minutes??) I do use it, and it runs about a week. It is huge compared to a smartphone, but that “months” myth make some people have unreasonable expectations. It had that effect on me.

Oh, and it does crash. OK, it doesn’t _crash_, it just resets. But it’s the same. It’s unusable for a few minutes when it does that. Again, people who say “it doesn’t crash” are probably using it much less than a PC. I use it about the same, and I can tell you that my PC crashes a lot less.

About distractions, well. Unless you count the crashes, I guess you’re right - up to a point. I mean, there are thousand documents on my Kindle to read. If that’s not a distraction, I don’t know what is. :-]

It does run a PC operating system. Of course. http://www.turnkeylinux.org/blog/kindle-root What do you smoke? 😀

Simon Anthony says:

I have been using the microwriting system since the days of the Microwriter and have worn out my AgendA, so I have written an iPad app, with the support of Chris Rainey. I am about to offer it up to Apple for Beta testing, but the website is live and anyone interested can take a look and send me emails from the site http://siwriter.co.uk

Comments wanted !

Many thanks.

Simon Anthony ( August 2013 )

Stanislav says:

Dear Simon Anthony,

This is beautiful work, and is a considerable improvement over the abomination of QWERTY keyboards on touch screens. However, the very concept of a keyboard without tactile keys is a serious industrial mistake, not unlike leaded gasoline. It is likely that multiple generations of people will end up paying for it, with their physical and mental health.

Yours,

-Stanislav

fenn says:

Traditional chording keyboard text entry is limited to about 2 characters per second at maximum, slower than even a typewriter keyboard. It’s just hard to press down all the buttons any faster than that. The Microwriter uses a scant 5 buttons, for a maximum of 5 factorial = 120 combinations. This tiny number of unique inputs limits the 5 button chorder to per-character input. It’s incapable of whole-word input such as used in stenography, so it will always be painfully slow to use.

However, human hands have 22 degrees of freedom, giving a theoretical maximum of 44 factorial = 2658271574788448768043625811014615890319638528000000000 two-handed combinations. This enormous potential is at hardly utilized even by stenography, with its two rows of keys, but it’s at least enough to type every word stem in the english language. Once you have a sufficient number of inputs (I like the design of http://homepage2.nifty.com/perky/index.htm ) it then becomes a tradeoff between time invested in learning to use the device and time wasted by not knowing more advanced key combinations. One could spend near infinite amounts of time learning and creating more and more key combo to phrase mappings, so how much time should one invest in memorizing key combinations?

The reason most people haven’t gotten interested in stenography or chording keyboards is that there is no ready-made path to just start using one. The common perception is that there’s no money to be made by selling weird keyboards for productivity. You have to build your own out of a pile of switches and wiring. This is really a pathetic situation considering how simple the technology is and how easy it would be for an entrepreneur to get started.

If you’re interested in using chording keyboards today, development of an open-source stenography platform has begun over at http://ploversteno.org

MDude says:

Do you think something like Ponoko would help? I think they only produce unassembled kits, but that seems less intimidating than having to produce a device from scratch.

Stanislav says:

Dear MDude,

Maybe. Or eMachineShop. Or the like.

Keyboards are surprisingly hard to get just right from a mechanical point of view, though. And the materials need to be of top-notch quality to stand up to years of use and abuse.

Yours,

-Stanislav

Toafan says:

No, five buttons does not give you five factorial combinations. Each button can be either up (unpressed) or down (pressed); so one button gives you two possible states (two to the first), two buttons gives you two times two is four possible states (two to the second) (while the first button is up, the second button can be either up or down, and the same when the first button is down), three buttons gives you two times two times two is eight possible states (two to the third), and so on. Five buttons would give you two to the fifth or 32 possible states–which is just about enough to fit the entire English alphabet and some interesting punctuation, by the way.

(I’m slightly embarrassed that I had to actually work it out.)

I’m not sure where you get 22 degrees of freedom for the human hand, but even with that number, if one degree of freedom is state-A-or-state-B, using both hands gets you a number ‘only’ fourteen digits long (as opposed to that unreadable easily-twenty-digit-and-probably-lots-more monstrosity you posted), ‘only’ two to the 44th which is some 17 (US) trillion.

Of course, with both of those, you have to reserve one state (potentially two for two-handed input?) as ‘neutral’, ie not doing anything. This is more onerous with the smaller numbers, but it’s also completely unavoidable.

(TL;DR: your math is embarrassingly wrong, it’s two to the N, not N factorial.)

Interestingly, the Microwriter actually pictured above appears to have six buttons (which gives two to the sixth = 64 possible states), but the documentation shown seems to only picture five. Not sure what’s going on there. Maybe the sixth button is used as some sort of “mode locking” button, to get two groups of 32 possible states each used for something different.

Jason says:

Interesting. Thanks.

Near says:

So true

Martin says:

Reminds me of Steve Roberts who devised a system (in the late 80s) to type out articles in binary while cycling.

http://www.recumbent-gallery.eu/computer-recumbent-bike-by-steve-roberts/

Thanks for derailing me to try to come up with some other novel input devices and going on long bike tours…

Bill Buxton says:

Interesting comments - much to agree with, but also others that I would question. Yes, Engelbart was unquestionably extremely important in his contributions to interaction, and I very much like that you point out that “easy to use” was decidedly not his objective. However, your statement, “Arguably, he is single-handedly responsible for the very notion of interactive, visual computing” is somewhat disrespectful of the arguably even greater contribution of the (earlier) work from Lincoln Lab (http://www.billbuxton.com/Lincoln.html). The accomplishments of one does not diminish the other. So, while I really like your pointing out the importance of appreciating our history, it is even more interesting when we begin to appreciate its full richness.

You write, “Modern computer engineering is kazoo-only, and keyboards are only the most banal example of this fact.” I find this puzzling, since the keyboard is one of the things that still does require a high level of skill to operate. And if your case is that it requires two hands, the little acknowledged fact is that so did Engelbart’s. His physical keyboard had 7, not 5, buttons: 2 on the mouse, operated by his right hand, and 5 on the chord keyboard, operated by his left. The encoding that he used was essentially 7-bit ASCII.

Your contrasting Engelbart’s chord keyboard with the Microwriter is useful in that it highlights the fact that all chord keyboards are not created equal. The coding on the Microwriter was much easier to learn and use. But then, from one possible reading of your essay, to be consistent, you might hold that against it. (I know you are not, I am just trying to make a point regarding the questino of ease of use: it does not have to imply going the path of the kazoo rather than violin. The violin is not made more diificult to learn than is neccesary to serve the full potential of its purpose. That helps us zero in on the real issue: the question has more to do with the the purpose is, and how the tool can best help the human in realizing their full potential to achieve it. And, the less that operation of the tool takes away resources from focusing on that purpose, the better.)

As for one of the comments that says that the best that one can do with a chord keyboard is two characters a second, may I suggest that you count how many notes Dizzy Gillespie could play in a second on his 3-button chord keyboard, a.k.a. his trumpet. In fact, the fastest text entry on a keyboard of any type has been accomplished using a chord keyboard.

Finally, if you want the details of how Englebart’s chording worked, or to learn about other chord keyboards - including the first “typewriter in your pocket” (made by a guy named Livermore in 1857!!!), see http://www.billbuxton.com/input06.ChordKeyboards.pdf

If you want to see more images of the Microwriter, including the CyKey and Agenda, as well as documenation etc., or any of the many other chord keyboards that I have in my collection, see: http://research.microsoft.com/en-us/um/people/bibuxton/buxtoncollection/

My closing comment is my oft repeated mantra: everything is best for something and worst for something else. We only begin to understand a technology or technique when we know both sides equally well, and the grey areas in between.

Thanks for initiating the concersation, and providing the opportunity to comment.

Brian Dunbar says:

I find this puzzling, since the keyboard is one of the things that still does require a high level of skill to operate.

I question this assertion.

We’ve all watched children pick up and use a keyboard and mouse: click, type, click again. This does not appear to require a high level of skill.

Tom says:

Well yes Brian, if you put it like that maybe so.

I’ll be off to hire a load of children to replace all of my programmers as there is clearly no difference in speed, familiraity of how to do stuff with it or anything at all between the two.

After that I’ve decided to stop thinking about piano lessons as I earlier saw a child clicking away on one and this action did not seem to require a high level of skill.

Cosman246 says:

Very interesting ideas, as usual, and hits the nail on the head!

Cosman246 says:

The only problem I see is that I’m left-handed. Also, I wonder how things like the Meta key would be replaced or represented by this

Stanislav says:

Dear Cosman246,

The second (lower) thumb key on the Microwriter was used as a “meta” key.

Yours,

-Stanislav

will_a says:

The “chorded keyboard and mouse” combination is actually incredibly prevalent in computing today. Not that a different keyboard is actually used (though sometimes enthusiasts will obtain modified versions of the standard keyboard, but the basic template is the same). Rather, the software applications treats a standard keyboard as a chorded keyboard.

What software applications? Video Games. Particularly First-Person Shooter (FPS) and Real Time Strategy (RTS) games, which require very fast and precise movements. The WASD+Mouse combo for FPS games has proven to be highly effective, and it is “chorded” in the sense that one can use the different movement keys (W,A,S,D) in combination to effect 360 degree movement, and they can also be used orthogonally with other action keys (reloading, firing, opening doors, etc.). RTSs function similarly (even if the gameplay experience is radically different).

The performance boost that this mode of interaction offers makes a big difference in gaming, because the flow of play could change in microseconds. Because development operates on larger time scales, those microseconds aren’t noticed (even if, over time, they actually do make a significant difference) Programmers in the main will only care about having an efficient UX setup once we have development environments which have the speed and interactivity of video games.

Stanislav says:

Dear will_a,

> Programmers in the main will only care about having an efficient UX setup once we have development environments which have the speed and interactivity of video games.

You are quite right about this. This is just the kind of environment that I am trying to create. Programming should be a dynamic and real-time experience, like shaping a ball of plasticine.

Yours,

-Stanislav

Jack says:

What? Are you now arguing that complex computing and planning tasks should now be made mindlessly simple like playing with silly putty?

Designing software, like designing a skyscraper, planning brain surgery, should in fact become the opposite of playing around. They require thought, planning, accuracy.

Like others have said, the keyboard already is professional equipment and takes years of learning to become truly proficient.

The problem device, the one that focuses everything on silly-putty ease of use at the expense of sophistication, is the touch-screen.

**** IM GEEK BASIC V1 **** » Engelbart’s Violin says:

[…] dazu in diesem Artikel bei loper-os.org / via Presurfer Kommentare […]

ASV says:

http://sethsandler.com/multitouch/community-core-vision-guide/

If there’s not already some way to use ccv to do this, the programming

of such a thing would be beyond my capability but I’d love to test it

out. I have a bunch of webcams just laying around, anyway.

Brian Dunbar says:

From the ‘Missing the Point’ department …

Perhaps you are now sitting in front of your lovingly-maintained heirloom IBM “Model M” keyboard

You can get _new_ Model M keyboards - Unicomp licenses the design from IBM.

It is tempting to find a chorded keyboard to supplement my existing setup.

Stanislav says:

Dear Brian Dunbar,

I’ve seen the Unicomp keyboards. The build quality falls somewhat short of the original.

Yours,

-Stanislav

Brian Dunbar says:

The build quality falls somewhat short of the original.

I will allow this is true. It is still miles better than the keyboard the IT department puts on your desk by default.

Chris Smith says:

Have you tried the very high end Cherry keyboard such as the G80-3000MX?

http://www.cherrycorp.com/english/keyboards/Office/G80_3000_MX/index.htm

I had an IBM model M for about 10 years until I got a PC without a PS/2 hole to poke it in. Very depressing. It was replaced by a G80 which was great, but the mechanical switches and side of a desktop PC both annoy my wife.

All were recently replaced with an old ThinkPad T61 which is quite good as well (for a laptop).

For the keyboard obsessed, there is a nice web site for you here:

http://deskthority.net/wiki/Main_Page

Stanislav says:

Dear Chris Smith,

You can use the PS/2 boards with an adapter. This one is guaranteed to work. I am happily using a keyboard which is older than I am, and intend to do so for as long as I live. The thing is nearly indestructible.

Yours,

-Stanislav

Cosman246 says:

I’ve been trying to find out how to get Meta key keycaps, and perhaps Hyper and Super keycaps as well.

Or maybe (gasp) a Space-Cadet Keyboard

Jon says:

Unicomps are IBM keyboards. Unicomp bought the actual tooling and machinery from IBM. They aren’t just making licensed clones.

A late reply, but this should be cleared up.

JonB says:

September 28, 2016 at 11:17 am

I have a Unicomp keyboard, bought at some great expense.

This has a buckilng spring inside each key, but underneath it all is an evil membrane. Unless the Model M also uses a membrane, they are not the same. The Unicomp feels like a Model M, except its body creaks. However, the issue for me is that three of the keys are suffering from keybounce for some inexplicable reason, and because they are not discreet keyswitches, I cannot swap them out. And this keyboard is not even two years old, and has only had very light use.

Obviously, I recommend not buying one.

Back on topic. I have a MW4 sitting in my loft, along with a TV adapter and all documentation. Thanks to this interesting article, I am now planning to pull it out of storage and have another go at chorded typing. 🙂

Stanislav says:

September 28, 2016 at 11:44 am

Dear JonB,

I recently purchased and restored an IBM Model F, circa 1984. There are no membranes in it, and all of the parts - including the cylinders and pistons - come out for cleaning. (Use an ultrasonic bath, they’re great.) There are no fewer than three sheets of steel in it - you will need to clean, sand, paint. Use “appliance epoxy” for the plastic face, it gives a nice texture. I heartily recommend the “F”. There are no exposed electrical contacts, it laughs at dust, moisture, and will probably outlive me. And the mechanical action is second to none.

Wong-Cornall makes a very decent controller (you will need to desolder the ancient one, replace with Wong’s or your own, and tune the capacitative sense circuit.)

Yours,

-Stanislav

Weekly List Bookmarks (weekly) | Eccentric Eclectica @ ToddSuomela.com says:

[…] Loper OS » Engelbart’s Violin […]

Chris Smith says:

Interesting and slightly related - an application for a similar device for tablets:

http://www.maindevice.com/2012/05/28/lenovo-slider-keyboards-tablets/

Theo says:

Very interesting article. The piece about the comparison of a child’s view of programming verses what it is in reality I can relate to somewhat. I eventually went to work in the salt mines then later in life traded that for creating my own salt mine and now spend most of my time working in that instead.

However I find my biggest disillusionment from my younger self is the gradual erosion of available time the older I get.

Before you even factor in the tools used to make what ever it is you’re making I find the above to be the biggest obstacle. Sadly life seems to creep up on you (well it’s not all sad, much of it is good but anyhow).

[…] Engelbart’s Violin Очень интересная статья о том, почему и куда исчезают профессиональные “железки”, а замещают их понятные массовому пользователю продукты. Они требуют долговременного обучения, зато позволяют здорово повысить эффективность работы. […]

Scott Locklin says:

I’ve always been fascinated by chording keypads, but never eccentric enough to buy one. I was particularly interested at the dawn of portable computing: I owned an HP95LX/HP100LX. It was a very well designed pocket computer from the 90s, which ran DOS-5, and had very low power consumption (it would last two weeks on AA batteries, with very heavy use).. It had a very good symbolic algebra system in Derive. I used to use that to calculate trace formulas and such. I even ran emacs on it and built some C and Fortran doodads I’d use on a big computer later. The big drawback was the keyboard (which, in hindsight, was/is embarassingly superior to something like the Ipad interface). I figured a chording keypad would work very well with a gizmo like this. Cell phone type devices would also benefit from chording input for power users, though there is no way you could convince a consumer numskull to use one.

Re: some of the comments: I bet if some Korean starts winning Starcraft championships using a chording keypad, they might get some traction with the idea.

Also, I bought myself a Das Keyboard a few years ago, for the home gizmo. Not perfect, but a lot better than the unholy horror of using a mac chiclet keyboard.

I hadn’t realized Engelbart had advocated/invented this as well. I guess I am not surprised.

Stanislav says:

September 12, 2012 at 10:05 pm

Dear Scott Locklin,

I too (briefly) owned the wonderful gadget of which you speak. And I am quite disappointed at the complete lack of anything recognizable as a successor to it. Modern computing progresses strictly in the “point and grunt” direction; the reasoning seems to be: why should a $400 device for viewing porn and cat macros come with a keyboard?

The gamer crowd eagerly snaps up various programmable keypads, like this one. Still no one shows the slightest sign of being interested in resurrecting chording for text entry.

Musical instruments are still made and sold, and sometimes learned, by sheer force of tradition; but makers of computer hardware reckon, probably correctly, that the mass market cares not a whit for human-computer interfaces that demand a similar learning commitment from users. Which is a crying shame. Millions of people are destroying their hands struggling with chiclets (and miserable virtual keyboards on touch screens) for no logical reason at all.

P.S.: Derive apparently lives on in the firmware of the TI-89 calculator. A rather fine machine, though quite mutilated in its latest two incarnations. (If you buy it, get the original version with the blue arrow keys. The new ones feel bulky and cheap, and have an appreciable boot lag - quite a feat for a pocket calculator! Despite a much higher clock speed…)

Yours,

-Stanislav

Scott Locklin says:

September 12, 2012 at 11:25 pm

I haven’t found a reason to purchase one of those TI calculators. My HP gizmos still function (I still have three of them, though only one has a working battery cover) if I needed one of those things, and the last time I checked, they had more capabilities than the calculator does. I really don’t do much with symbolic math any more that can’t be solved with pencil and paper.

It is a tragedy that there is no heir to the HP100LX. Someone was talking about a short run version based on a low power 486 chip, but I don’t think anything came of it.

I guess if I become an APL whiz, the keyboard won’t be holding me back much any more. Every damn character represents a whole bunch of thoughts.

fogus says:

September 13, 2012 at 11:28 am

Spectacular essay. It makes me feen for a simple chorded device to hold in one’s hand and casually take notes during meetings. I’d be happy with a USB pen drive with a button allowing Morse Code note-taking.

Also, thank you for the pointer to Bardini’s book. It was a joy.

Chris says:

I found myself respectfully disagreeing with many of your ideas. The joy I feel writing code today, solving problems and building things (ideas) is identical to what I felt as a fourth grader sitting in front of a BASIC terminal. I suspect you are taking your own childhood feelings toward programming and projecting them into everyone else. As for your ideas about professional grade keyboards, I’m not quite sure what a gold-plated, ebony keyboard would do to help you write better code; a Stradivarius and a Yamaha are both cellos, but the analogy of professional grade physical things breaks down for software engineers, whose domain is thought-space. My work machine has far more cores and RAM than a typical computer user’s.

Stanislav says:

Dear Chris,

> The joy I feel writing code today, solving problems and building things (ideas) is identical to what I felt as a fourth grader sitting in front of a BASIC terminal.

I am glad that you still feel the childhood joy of programming. Since I know nothing of your work, I cannot say whether it is because your problem domain presents you with unbridled opportunities for creativity, or if it is because you are the kind of person who enjoys simple, repetitive tasks - most computer programming anyone is actually paid for doing consists of the latter.

> I suspect you are taking your own childhood feelings toward programming and projecting them into everyone else.

I am under no illusion that everyone agrees with my perspective, but I have run into quite a few people who do. Some of them have found this site, and occasionally comment here. Others reminisce wistfully and post cowardly manifestos of surrender to cultural decay:

“6.001 had been conceived to teach engineers how to take small parts that they understood entirely and use simple techniques to compose them into larger things that do what you want. But programming now isn’t so much like that, said Sussman. Nowadays you muck around with incomprehensible or nonexistent man pages for software you don’t know who wrote. You have to do basic science on your libraries to see how they work, trying out different inputs and seeing how the code reacts. This is a fundamentally different job, and it needed a different course.”

Like most computer programmers, I grew up with the “edit, compile, pray, debug cycle,” QWERTY keyboards, crashable software, the C Machine, and other abominations. But unlike many, I refuse to make peace with these idiocies.

> As for your ideas about professional grade keyboards, I’m not quite sure what a gold-plated, ebony keyboard would do to help you write better code…

The fact that you bring up “gold-plated, ebony keyboards” in response to this article shows that you have thoroughly, artfully missed the point. The user interfaces (and other design details) of the computers we have now are historical accidents; particularly unfortunate ones, at that. There is no reason why mankind must remain forever doomed to operate electronic computers using an interface designed for manual typewriters.

Fish may never understand water, but human beings eventually understood the existence and properties of the air they breathe. You are a human being, and so you are able to think critically about your environment, including those aspects of it that you have taken for granted since birth.

> a Stradivarius and a Yamaha are both cellos, but the analogy of professional grade physical things breaks down for software engineers, whose domain is thought-space.

The difference between what is now on your desk and what is possible - in fact, what has already existed in the 1980s - is far greater than that between the Stradivarius and the Yamaha. The fact that you may never have experienced a truly high-quality programming environment, and did not grow up with (and therefore find it difficult to appreciate) a chording keyboard, does not change this fact. All programmers today are cutting bits with dull knives. A certain degree of Stockholm syndrome comes naturally to most people, and so few complain. But it remains true that the modern computing environment is an atrocity against the human mind.

> My work machine has far more cores and RAM than a typical computer user’s.

Computers only come in two speeds. And I bet your 48-core monster rig still feels slow under everyday usage scenarios (e.g. the crock of shit that is Web 2.0 email, etc.)

Professional tools are not simply bigger and costlier than equipment intended for casual users. The difference does not consist solely of mechanical quality, either. I argue that professional equipment is such that rewards learning and dedication: infinitely customizable; entirely clean of mandated rote and repetition; certainly nothing like the click/drag/grunt nightmare that infests nearly all user interfaces presently in use.

You are not a fish; learn to see the water. A different, “dryer” world is possible.

Yours,

-Stanislav

fogus: The best things and stuff of 2012 says:

[…] Engelbart’s Violin — A beautiful post about keyboards and chording and enhancing the human potential. […]

Duncan Bayne says:

I don’t think that ‘user-friendliness’ is a useful concept when discussing UI design. It’s a conflation of two separate concerns: discoverability and usability. One can lead into the other, but frequently they don’t (e.g. in almost all modern GUIs).

I gave a brief presentation on the idea to RoRo a while back (notes on GitHub).

Russ Nelson says:

Do you want an Engelbart keyboard? The electronics and basic core of the software are there, using keymodules rather than paddles. I’m still working on a paddle version. I’ll sell you one for $100. It requires a PS/2 mouse, but will work fine with a USB->PS/2 adapter. Works with wheel mouse.

Stanislav says:

Dear Russ Nelson,

I might buy it. Let’s see it. What kind of key switches do you intend to use?

I should add that a properly-implemented keyboard must work with zero software support. (The PS/2 keyboard protocol is trivial to implement in a microcontroller.)

Yours,

-Stanislav

Russ Nelson says:

Marquardt key modules. I’ve since tried using paddles, and am not terribly pleased. Doug used a linear set of five piano-like keys, but I think that a bent keyboard with the keys underneath fingertips works better. Don’t have any photos of the current prototype.

I agree – the keyboard must be a USB keyboard / mouse combination that simply works with everything and requires no OS drivers.

Loper OS » RIP Douglas Engelbart. says:

[…] everyone that Engelbart invented the computer mouse, but they are largely silent on the matter of his having personally created almost every one of the concepts we think of as part of a standard hum…, including the very idea of an interactive graphical workstation. This is because a silent army of […]

Обзор свежих материалов, апрель-июнь 2012 | Юрий Ветров об интерфейсах says:

[…] Engelbart’s Violin Очень интересная статья о том, почему и куда исчезают профессиональные “железки”, а замещают их понятные массовому пользователю продукты. Они требуют долговременного обучения, зато позволяют здорово повысить эффективность работы. […]

SATURDAY | 13 JULY 2013 | The Mighty Marcus Reader says:

[…] of the need for computing systems to be easy-to-use was not irrational. As Stanislav Datskovskiy argues, Engelbart’s primary concern was that the computing system should reward learning. And Engelbart […]

jonesy says:

I arrived here via a succession of links that started from an essay

by Mike Hoye concerning the True History of zero-indexing. To all

involved along the way, to you, Stanislav, and the commenters, my thanks

for presenting new things and providing much food for thinking (to the

extent I might wrap my head around it.)

While I quite take the point about the Violin, at this stage in my life

it’s not for me, other than a Big Thing to remember when considering the

world around me.

Your comments on keyboards struck a nerve; mostly I use whatever I can

scrounge, that comes with other kit, or that I can afford - my cheapo

Logitech wireless set. To think, I learned touch typing in high school

in ’65 - the only class available apart from physics and English my

senior year. While I can’t remember the manufacturer, it had all the

normal adjustments and each key could be tuned to the typist. If one had

a weaker finger, the force necessary to depress the relevant keys could

be lightened by, among other things, changing the attachment points of

some of the springs and pivot points. To this day I find the whole

contrivance remarkable.

Don’t even get me started on the whole GUI/UX stuff. Too many of those

doing it are up-screwing it wholesale - all the research into

perception, action, the whole human factors corpus, tends to be ignored

or abused in exchange for shiny. In some ways the usability and metaphor

have been declining since GEM.

Thanks again for the fine dining.

Alan Kay says:

Pretty good essay! You missed my point about Engelbart’s chord keyboard (I loved it). I was pointing out that most people are not willing to invest even what it takes to learn to ride a bicycle today on anything new – nor are marketeers. The basic idea is that – as with musical instruments – there needs to be a transition from just love of music and doing it (e.g. by singing and dancing) to a little more work to synergize with the physical amplifiers that can allow us to do much more.

And, many of your other commenters were quite right that personal computing did not start with Engelbart. Personal computing came from an entire research community of which Engelbart and his group was an important part. If one were to search for the first example that is undeniably like modern personal computing, one would have to pick Ivan Sutherland’s Sketchpad system done at Lincoln Labs in 1962.

Cheers,

Alan

Alex Byasse says:

I don’t understand what you mean by the lack of professional computer programming equipment, we have different tools to other professions but there is definitely a big gap between commercial tools and personal: Eg. Visual Studio Professional; Massive blade machines run with a Linux server. Not to mention your point about the tedious work, your obviously not smart enough to position yourself into a position of creativity. There’s plenty of companies out there that look for the industry leaders to work on very creative works?

Leo Richard Comerford says:

But the difficulty of learning a different style of keyboard is only secondary: the main issue is that, for programmers, a one-hand keyboard is the solution to the wrong problem, or at least to a problem of secondary importance. All else being equal a one-handed keyboard is always likely to be a lot slower for typing than a two-handed one. So the combination of one-hand keyboard and mouse allows you to type slowly and point quickly and accurately: the advantage is that it lets you do both simultaneously or near-simultaneously, with no switching time caused by having to reach a hand from keyboard to mouse. Still, it’s the wrong way around for tasks like programming which are usually typing-heavy: most of the time programmers would be much better served by having the ability to near-simultaneously type quickly and point slowly. Fortunately, the hardware to do this is already in fairly wide use: keyboards with pointing sticks, and/or trackpads under the spacebar which can be thumbed without taking your hand off the keyboard.

Ideally you’d want to be able to switch between both typing slow+pointing fast and typing fast+pointing slow modes. In fact it would be fairly easy to make that possible even without a separate one-hand keyboard: https://plus.google.com/105224327306964621564/posts/51JkbiocpnU . If you do want to or have to use a one-hand keyboard, many of the commercially-available “gameboards” are perfectly able to act as such, often including full NKRO to allow chording.

Stanislav says:

Dear Leo Richard Comerford,

A chording keyboard doesn’t have to be one-handed. See, for instance, this one.

You can try using an ordinary PC keyboard as a chorder right now. It is an ergonomic nightmare, given as it involves contortions of the hands. A chorder should give the hand a place to comfortably rest, and make lateral movements of fingers unnecessary.

As for the ‘gaming pads,’ they are of the same abysmal quality as the currently-produced conventional PC keyboards. Some people can put up with mushy rubber dome switches - not me. Clicking keys only please.

Yours,

-Stanislav

Leo Richard Comerford says:

A chording keyboard doesn’t have to be one-handed. See, for instance, this one.

Sure: the traditional stenotype writer is another two-hand chording keyboard. Things like Plover and the coming Stenosaurus are working to bring steno out of its isolated, overpriced niche. But steno’s somewhat-syllabically-based shorthand system (or family of related systems plus private tweaks) is a big bag of hurt, and in addition probably unsuited for code or anything other than natural-language input. (Also *partly* redundant with things like autocomplete or predictive text.) The most obvious alternative is a one-letter-per-chord system as used on most one-handed chording keyboards. But stroke-for-stroke (defining a single keyboard chord as one stroke) chording is apparently significantly slower than non-chorded typing*, so any one-letter-per-stroke system will be slower than QWERTY. And speed probably is more or less the only possible reason to use two-handed chording on the desktop as a means of text input for users without relevant disabilities. Unlike one-handed chording you’re not keeping a hand free; you’re not mobile like a Twiddler or Microwriter user; and since steno chords, at least, are more straining on the hands than single QWERTY keypresses, you’ll likely be worse off ergonomically unless you can average significantly more than one letter per stroke. There is an answer, however: orthographic-shorthand keyboards like that of the Velotype/Veyboard, which allows you to get out 1-3 characters per chord (plus omitted spacebar-presses). It’s not as fast as a stenotype at getting down a quick and dirty transcript of spoken English, but it’s much more suited to handling foreign languages, special characters, odd capitalisations and so on.

The two-handed chorded keyboard may be a violin, especially if you look at syllabic, dictation-focussed systems: the courses to reach professional, 225 WPS standard on the stenotype take 1-3 years and have dropout rates like 90%. However it certainly don’t seem to be Engelbart’s violin: afaik there’s no chording on the two-hand NLS keyboard, and I’m not aware of him experimenting with two-hand chord keyboards at all. If so, you can see why. For text input on the desktop the only advantages of two-handed chording are speed and maybe ergonomics, character repertoire or support for some disabled users. For most users who can touch-type, two-handed typing speed is probably not something which often holds them back seriously. (And of course if a programmer is regularly bottlenecked by his touch-typing speed, it’s likely a sign that something is wrong with his programming, and/or his editor or language…) It was reasonable for Engelbart to focus his efforts, and the efforts of NLS learners, on other things. And, both then and now, the transition time between mouse use and typing on the two-hand keyboard is the bigger nuisance.

That said, chording on a two-hand keyboard is also useful as a way to increase the possible repertoire of keyboard shortcuts (and maybe of characters), or to allow the two-hand keyboard to be used as a one-hand keyboard (making the separate one-hand keyboard of NLS redundant). And additional typing speed is certainly a good thing to have.

As for the ‘gaming pads,’ they are of the same abysmal quality as the currently-produced conventional PC keyboards. Some people can put up with mushy rubber dome switches – not me. Clicking keys only please.

Well, the Razer Orbweaver has mechanical keys (Cherry MX Blues apparently). I’m not sure if it even has full NKRO though.

* A high-end professional QWERTY typist’s 80-95 WPM speed equates to 6.6-7.9 strokes per second. The Guinness World Record for steno WPM was achieved with a stroke rate of 4.8 per second, and apparently 4.5 strokes per second can be considered “VERY FAST” even by the standards of steno professionals. (Apparently some stenographers can get beyond 7 strokes per second, but these should probably be compared to the 120 WPM+ elite of QWERTY typists, who are doing 10+ strokes per second.)

Leo Richard Comerford says:

The upcoming King’s Assembly will tick both the one-hand-keyboard-with-mechanical-keys and the two-hand-keyboard-with-pointer-controller boxes, all going well. I’m not sure how well the keyboard-as-mouse concept will work, but it doesn’t matter much as you’ll be able to set a thumbstick to control a mouse pointer anyway.

Stanislav says:

Dear Leo Richard Comerford,

Clever. Can’t say I like the thumbstick mouse, though.

Yours,

-Stanislav

Phil says:

This post really struck a chord with me (pun not intended) since I have been thinking about ways to improve my current development workflow. What do you think about using dual five-button mice? You would use one mouse (Mouse A) for movement and clicking, and you would use the other mouse (Mouse B) as a chorded keyboard. I used to have a Microsoft mouse with two main buttons, a scroll wheel (which can function as another button), and a button on each side. You could input regular text commands with Mouse B and control commands with Mouse A. Does anyone have any reccomendations for wireless five-button mice?

Stanislav says:

Dear Phil,

A keyboard which slides easily around on the table when you use it is an ergonomic nightmare. Count me out.

Yours,

-Stanislav

Anthony says:

Interesting read! I studied type interfaces in my one of my HCI classes and made this as a class homework.

Bram says:

Interesting read. My first typing was done on a chorded two handed typewriter, a braille machine. However, since the time I start using computers I used a normal typewriter keyboard. Braille is usually one stroke per character, not counting in abbreviated codes for multiple character sequences that are language specific (e.g. English grade 2 braille). Despite the lack of finger movement on a braille keyboard, I’ve always been faster on a normal typewriter keyboard.

That being said, I’m way faster entering braille on a touch screen keyboard compared to a qwerty on screen keyboard. However, I hate any form of non-physical keyboards with a passion.

penlu says:

It seems to me that character-by-character typing on a chorded keyboard would actually be slower than typing on the qwerty board I’m using. Besides the figures presented in Leo’s post I would also like to observe that for example playing a sequence of chords on a piano is significantly slower than playing a succession of individual notes as in a scale.

I think the major speed-limiting factor of a five-finger chorded keyboard is the requirement that up to five keys (usually, I suppose, around two or three) be pressed and then released before the next character can be chorded, whereas on a keyboard a finger can be moving to type the next character before the finger that typed the previous is ready to go again. (Try typing j repeatedly, then trilling i and j. Rough measurements for me seem to indicate I am pretty much exactly twice as fast doing the latter.)

Some keyed input with reduced synchronization requirements should be faster. I think for example splitting a keyboard into two components on which the hands type separately (every keystroke pair being interpreted together as another input) would present less of a slowdown while effectively doubling bandwidth and also being relatively easy to commit to muscle memory.

Dave says:

With the hindsight of 2016, I’d say the keyboard turned out to have been a violin all along; its presence is now largely limited to professionals and interested amateurs, while the rest of the world appears to have eagerly moved on to tooting the vuvuzela of emoticons…

Josh says:

In case anyone is interested, I’ve made a free and open source project, written in Common Lisp, and extends Engelbart’s one handed keyboard. It has a different alphabet, but allows for both one and two handed typing and allows for powerful mnemonic shortcuts. Currently runs on Linux.

I was looking for a place to buy a chorded keyboard like the original Engelbart design, but couldn’t find one! So I rolled my own. It’s currently prototype stage, but very usable and powerful. You can make your own or buy one from the website. More designs coming soon.

Let me know what you think, I’d love to get some feedback!

Stanislav says:

September 26, 2016 at 10:39 am

Dear Josh,

Please post the second comment again, it seems like it got eaten by the spam filter.

Yours,

-Stanislav

Simon Anthony says:

If anyone is still interested, I have recently updated my SiWriter code to run on the larger iPhones as well as the current ios . A recent upgrade broke my code, but the soon to be released revision > 3.2.0 on the Appstore will fix the ‘missing keypad’ issue. This new release is awaiting review as I type. I would be pleased to hear thoughts and comments on this app. Yes, it still doe not have any haptic feedback, but a small iPhone screen does reduce the chance of your fingers wandering off the pads - which can be widened ! The app caters for left handed users as well, and has speech output - handy if you have a speech impairment.

Thomas Kelsey says:

Programmers are different from composers in that the tools they use (computers editors etc) are used by the general public as well; perhaps a better analogy would be with professional drivers like Uber drivers, who might be more skilled than most but drive mostly off-the-shelf cars.

Speaking of chord keyboards, I’ve developed software which allows you

to use a normal keyboard as a chorded keyboard, like the MicroWriter

except without having to buy new hardware.

To use your analogy, it’s like being forced to use a kazoo, but hacking

it into a violin.

You can see a video of it in action here.

Stanislav says:

Dear Thomas Kelsey,

> use a normal keyboard as a chorded keyboard

Sounds like an ergonomic nightmare, TBH.

Do you use this for everyday work?

Yours,

-S

Thomas Kelsey says:

It was certainly challenging working out typable combinations of

keys.

The rule is that you type each key with the same finger you use for that

key when touch typing, so the only potential ergonomics issue is awkward

combinations like S and Z or Q and B.

i don’t use it for coding but I use it for text.

Tom

Florencio says:

Have you considered politics?

The subject of skullduggery in professional programming as introduced in

the beginning is abused in such a cynical way as to be downright

appalling. You weave a heartwrenching yarn about the destruction of a

youthful programmers dreams and imagination, to be replaced by an

crushing, rotten machine (Welcome my son, etc. etc.) devoid of

creativity. Which all very emotive and captivating, but then suddenly

all that gets thrown by the wayside and that disgust and anger you’ve

harvested in the reader gets unfairly offloaded onto the keyboard as the

writer rides those emotions into the rest of the article. Cunning

rhetoric as that may be, it leaves an awful taste in the reader’s mouth

once one has realized how cynical the nature of it is.

Now, the idea you propose in the article has merit: Peripherals

with a high skill ceiling should have a place in computing.

However the way in which you go about presenting this idea isn’t just

flawed but misses the forest for trees in a different forest entirely.

An input peripheral is not to the programmer what an instrument

is to a musician. Therein lies the mind. It is the mind with which the

programmer does programming. It would not even be fair to say that the

peripheral is the means with which the programmer bridges his thoughts

to the machine, for that is the role of the language. If a programmer is

merely “cranking the organ grinder” as it were, that is because the

programmer is not thinking–the keyboard has no more to do with it than

the programmer’s socks do.

In defense of the keyboard, once could hardly call keyboard use

unskilled. It takes a great deal of coordination and mental memory to

learn to touch type quickly. I’m sure we’ve all experienced the

discomfort of watch a parent or colleague slowly find-and-peck their way

on a computer. More importantly, the keyboard is already effective and

versatile at what it does. The limitations imposed by our present

computing ecosystem are, as you expressed in your introduction, a matter

of an outdated, broken Paradigm. Not peripherals.

Stanislav says:

Dear Florencio,

Which all very emotive and captivating, but then suddenly all that gets thrown by the wayside and that disgust and anger you’ve harvested in the reader gets unfairly offloaded onto the keyboard… …how cynical

Out of curiosity, have you read any of the other material on my WWW? Or only this essay?

The reader is indeed encouraged to build up his healthy emotions of disgust and anger – directed properly at the entire sewer which passes for “the state of the art”, and not merely one particular pile of shit; and at the culprits as a class. Though it is quite impossible to escape dealing with particular atrocities. And the QWERTY crime against muscles, joints, tendons, and productivity as a whole, is by far not the lightest among these atrocities.

…An input peripheral is not to the programmer what an instrument is to a musician. Therein lies the mind. It is the mind with which the programmer does programming.

Is the computer which you program telepathically-operated ?! Where can I buy one like it? Mine, unfortunately, is operated via a keyboard. And IMHO the finest keyboard available; but nonetheless this device is not only central to my physical experience of operating the machine, but is most certainly the bottleneck in the process of getting bits from my head onto the disk; and requires day after day of repeated, unnatural contortions – while a chorder would not.

And it isn’t even that building a chorder is difficult; simply, the proper time to learn chording is in one’s first, rather than fourth, decade of life.

…In defense of the keyboard, once could hardly call keyboard use unskilled. It takes a great deal of coordination and mental memory to learn to touch type quickly.

An untrained user “hunts-and-pecks” several times faster on first contact with the QWERTY than on a chorder. I thought this was obvious. As is the fact that the latter actually rewards training to a much larger extent than the former (e.g. stenographers routinely achieve error-free 200+WPM. Do you know any 200+WPM QWERTY operators?)

…a matter of an outdated, broken Paradigm. Not peripherals.

The peripherals are as broken as the rest of it!

What, I wonder, would you say to the (quite numerous) people who have lost the full use of their hands thanks to the QWERTY monstrosity? “Peripherals are already effective and versatile and great just as they are” ?

Yours,

-S

Florencio says:

My apologies for the formatting in that last post, it seems this website requires 2 line breaks

to create one in the finished post.

Verisimilitude says:

I’ve re-read this and all of the comments. It’s interesting to note how little has changed, sans those links falling to nothing.

What would it have been like if I had been put in front of an Endfield keyboard as a small child, instead of a typewriter monstrosity?

I was using a BAT chording keyboard and trackball as my primary input devices for roughly half a year; my goal was to avoid pain. I’ve more recently switched to a buckling-spring keyboard from Unicomp after the experience; now it feels the trackball is the worst for me. A chording keyboard tired its associated arm too frequently to use as a total replacement, but programming environments are also generally unsuited to it. I’m not convinced the typical keyboard is a torture device, but I’ve also used Dvorak since shortly after learning Qwerty and experiencing pain due to it. Typing seems a fundamentally unpleasant activity.

A chording keyboard is nice, Stanislav, but I’ve used them more between us by now, and they’re no panacea, nor were they claimed to be; I could’ve bought a pair to use and perhaps removed one of my primary complaints, but I instead chose to purchase a keyboard considered good, and it’s done a decent amount to relieve me of pain. I’d like to look into voice or sound recognition, a foot mouse, and to give my hands a total rest.

Regarding interfaces which reward learning, I want to mention my machine code development tool, the Meta-Machine Code (MMC). My first implementation was designed to be customizable past reason and also contains flaws I never fixed, the second learned from those mistakes, and the third does more to eliminate flaws with the design I’d not seen early enough with its predecessor. Each key on the keyboard is assigned to either an instruction or a control action, what an assembler would use disgusting little pseudo-instructions to achieve, and a targeting of the tool is only useful for one machine code. I’ve created a formal model and maximalist interface for doing a rare computing task, but it’s the best at doing it, eliminating most typing, errors, and other nonsense or drudgery. Rather than make the tool customizable, I’ve instead sought to reduce it in size and complexity to the point any user could understand and modify it directly, but I’m still a ways from the ideal, despite being closer to it than many could want.

I also take offense to the idea of representing and entering text as character sequences, and see no shortage of other disgusting historical circumstance worth putting to an end. Most every interface of modern computing is meant to serve itself and not its users, so edge cases abound without true solution. I know I’m going to be required to do this work myself, to get close to the ideals I want before my death.

I suppose my comment has by now become rambling, so I should stop here.

Name (required)

Mail (will not be published) (required)

Website

XHTML: You can use these tags: <a href=“” title=““> <abbr title=”“> <acronym title=”“> <b> <blockquote cite=”“> <cite> <code> <del datetime=”“> <em> <i> <q cite=”“> <s> <strike> <strong> <pre lang=”” line=“” escaped=“” highlight=““>

MANDATORY: Please prove that you are human:

51 xor 25 = ?

What is the serial baud rate of the FG device ?

Answer the riddle correctly before clicking “Submit”, or comment will NOT appear! Not in moderation queue, NOWHERE!

« May 2012 Update Project JMC »

Search for:

Bitcoin, by popular demand: 1NrrHYZMum2JaHJeSZufFiTqg9W8uNdfzM (Please verify PGP Signature !)

Copyright © 2022 Stanislav Datskovskiy · Any views or opinions presented on this site are solely those of the author, Stanislav Datskovskiy, and do not necessarily represent those of his clients, employers, or associates. All information on this site is provided as-is, with no warranties whatsoever.